Generally there is some truth in obvious answers. But often digging deeper leads to greater insight. For instance, in recent years countries in Central America have led the world in murders per capita. Gangs are one of several contributing factors. With greater urgency people have asked: why do youth join gangs? Perhaps the most common answer is poverty and a lack of jobs. My friend, sociologist Bob Brenneman, agreed that poverty is a crucial factor. But he made the important observation: not all, not even a majority, of impoverished youth in the same neighborhood join gangs. So, he dug deeper asking: why these youth? What is different?

In his book, Homies and Hermanos: God and Gangs in Central America, Bob describes joining a gang as a desperate grasp for respect. Repeatedly, the sixty-three ex-gang members he interviewed carried profound shame from painful years in especially dysfunctional families and other experiences of social exclusion. The honor and a sense of belonging offered by gangs had a special power of attraction for these youth. Bob’s digging led to this and other insights. It is a great book filled with captivating narratives and excellent analysis. I commend it to you. I also commend following his example—digging deeper rather than simply accepting conventional wisdom. For instance…..

Many use levels of wealth as the obvious and simplest indicator of quality of life—a rich county is a better place to live than a poorer one. In response to the question: How do we help the poor suffer less? The obvious answer is increase a poor individual’s income, or a poor country’s GDP. We might think of this as poverty line thinking—what matters is helping boost people above that line into a better life. I certainly had that mindset when I lived in Honduras. Granted, a certain amount of resources are necessary for thriving, but if we dig deeper this answer is not necessarily the best one.

Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson go deeper than the obvious answer in their book The Spirit Level. They combined various measures of well-being, such as life expectancy, literacy, infant mortality, incarceration, mental illness, addiction, social mobility, obesity and homicides, and found that, amongst developed nations the ones with the highest level of well-being were not the richest ones, but those with the lowest levels of economic inequality between the richest 20% and the poorest 20%. And those with the worst levels of well-being were not the poorest but those with the highest levels of economic inequality.

Levels of economic inequality

Note in this graph that Portugal and the USA stand right next to each other in level of inequality, yet if the graph displayed per capita income they would be at opposite ends of the graph and it would be Norway, not Portugal right next to the USA. If we went with conventional wisdom equating wealth with quality of life the USA and Norway would be best, and Portugal the worst. But in fact Portugal and the USA are next to each other, the worst, in the following graph of well-being.

Inequality is the key determining factor. Another way of making this point is to look at a graph that charts income rather than inequality. Unlike the above graph, there is no correlation between the two factors—the dots are scattered all over the graph.

What we observe in these summary charts matches chart after chart on the individual factors, and charts that compare states as well.

Thus, after digging deeper we observe that, in a general sense, the most important thing to do to help the poor thrive is not increase income levels but to lower the level of inequality. (Even as I write that sentence I resist. Something in me shouts out: “but raising incomes levels matter!” and protests: “This study is only of ‘developed’ nations.” True. There are countries, contexts, and individuals where increased resources are crucial. But, even in those situations inequality matters—poor people in a poor country with low inequality are better off than poor people in a poor country with high inequality.) Returning to the earlier poverty line image, we might conclude, certainly it is a good thing to help people get above that line, but we are missing something crucial if we only look at that one line and not also the line at the top that identifies the very wealthy. We must pay attention to the two lines and the gap between those lines—and seek to lessen that gap between the rich and the poor.

When one digs deeper you find not only better answers to the question asked, but discover important things you were not even asking. Here is a big one. As Wilkinson explains in a Ted Talk it is not just that the poor are worse off in countries with high inequality—those in the middle and the rich are affected to. All across the income spectrum people are affected negatively by high inequality. So, lowering inequality helps not just the poor; it helps all.

This calls for action. We can increase shalom for all by lessening the inequality gap. One response is at the macro level. Wilkinson calls for this sort of action in his Ted Talk—careful to give suggestions that those on the right could embrace and others that those on the left could embrace. Certainly these are worthy of our attention and effort. Again, however, digging deeper has value. What is behind this? Why does greater inequality lessen shalom? The Ted Talk does not answer address that question, but in their book Wilkinson and Picket do. After comparing data from various countries, their conclusion is: “Greater inequality seems to heighten people’s social evaluation anxieties by increasing the importance of social status” (43). Status competition increases, and with it shame for not measuring up. They make clear that this is not just an emotional or psychological issue. This shame and the stress related to status competition negatively impacts health and interpersonal relationships.

Shame. Our digging has brought us to the same place that Bob Brenneman’s digging brought him. What does this mean for us as Christian communities as we seek to help the poor (and everyone else) by addressing the problem of the large inequality gap?

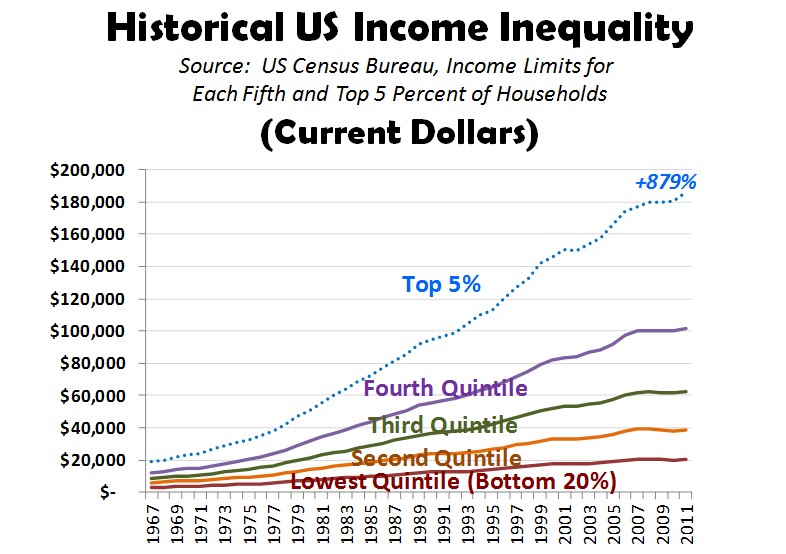

We can and should take concrete actions to increase income levels of the poor around us. But we simply cannot push people up high enough and fast enough. Even as we push people above the poverty line they still will face a larger gap of inequality than they would have thirty of forty years ago because in the United States in recent decades the gap has grown larger and larger; it is much larger than most think it is.

Clearly the United States, working from both the right and left, needs to address structural issues and lessen this gap. Christians should be involved. It will be a long challenging task. Yet, right now, today, Christians can take action that will have immediate impact—provide liberation from shame and buffer people from social evaluative anxieties.

- Let us proclaim liberation from the burden of shame through Jesus, using texts like Luke 7 and Luke 15. (Luke 7 magazine article, sermon; Luke 15 Bible study.)

- Shame is a relational wound and the healing must be relational. Let our churches be places of healing and protection from shame. Through this recent election season and now in the first weeks of the Trump presidency walls of division and status anxiety have increased. The need and opportunity for the church to center on Jesus, invite all to the table, and live out Galatians 3:28 are great.

- Of course, if the church is truly to be a haven and place of healing, then, in the words of former student Kathy Streeter, let us “refuse to let inequality enter the doors of the church.” We can be, as Jim Tune, another former student, writes, “an alternate community where things aren't measured by ‘performance’ or economic and social status…. In Scripture James warns against favoritism. I think the church may need to become more vigilant in guarding against this.”

- Let us, in the words of Father Greg Boyle, “stand at the margins so that standing there the margins will be erased.” Father Boyle talks as powerfully, and engagingly, as anyone I have heard on the power of kinship to dismantle shame and disgrace. Listen to this Ted Talk or this On Being interview and allow him to feed your imagination of how we can undo damage caused by the inequality gap through kinship.

- Refusing to let inequality enter the church means resisting consumerism and other forces that do so much to feed status anxiety.

Taking these actions to lessen the shaming power of the inequality gap will have multiplying impact. If the deep digging of Brenneman, Pickett, and Wilkinson is correct, these actions will have ripple effects touching many aspects of people’s lives—contributing to broader and deeper shalom.

To focus on shame does not mean to ignore economics. Many Christians who own businesses will sit in church this Sunday. They have great opportunities to address the inequality gap both through how they structure pay and how they treat workers. I look forward to writing more about this in the near future.

Let us not settle for superficial answers, and as followers of Jesus may we be in the forefront of addressing issues discovered through digging deeper.